Lights dim, shimmer, fade, and revive – pulsing with breath as if to match the steadily roaring grumble of a capacity crowd at the Paramount Theatre in Austin, Texas. Showers of raucous catcalls pour from all walls in rivulets of rage, furor, and nail-biting tension. This 1,324-seater is sold out, and people are looking for blood like sharks who have inhaled fear, thundering like sports fans who taste a touchdown or a piledriver with hands clapping against the backs of chairs and shoes stomping on concrete. The auditorium could almost crack open and swallow itself from stage to balcony.

The crowd spews choice phrases at the slightest show of weakness, and yet they’re prone to abject sing-song hypnosis and moments of crushing pathos, especially when their heroes melt under a collective magnifying glass of audience scorn. They’re oddly tame when an emcee takes the microphone.

AUDIENCE: DO YOU SOLEMNLY SWEAR TO TRY TO INFLUENCE THE JUDGES’ SCORING THROUGH YOUR UNBRIDLED ENTHUSIASM?

“Hell yeah!” the house echoes. But the audience is not worked up over a football game or wrestling match; they’re here for a verbose brawl, a battle of wits, metaphorical bloodsport, an endurance contest fought, won, and lost with the travel of words from mind to mouth to mic to the mob.

Believe it or not, they’re here for poetry.

The ringmaster has no clothes, so to speak, except for a porkpie hat and scrubby facial growth. He’s the zookeeper, word pusher, the Ayatollah of Slam-ola, guardian of the poetry-temple exchange rates. New York City poetry impresario Bob Holman speaks: “Hey hey hey! Everyone wants to know how come when you get these poems up here, these THINGS of beauty, which we have asked the whimsically selected judges to adjudicate for us, that these THINGS of beauty can become their numerological equivalents – doesn’t that mean that the life gets kicked out of it? Absolutely! It’s a poetry slam!”

JUDGES: DO YOU SOLEMNLY SWEAR THAT YOUR SCORES WILL BE BASED SOLELY ON YOUR OBJECTIVE EVALUATION OF THE POETRY AND PERFORMANCE, AND NOT HOW MUCH BEER YOU HAVE BEEN BRIBED WITH?

Jeering whistles clash with hands clapping, but Holman devours all responses: “This is a poem that is dedicated to all of us, all the poets who have come up here, read their poems, and gotten screwed! It’s called ‘Why Slam Causes Pain and Is a Good Thing’:

because slam is unfair

because slam is too much fun

because poetry because rules

because poetry rules

because I could do that

because everybody’s voice is heard …”

AND LASTLY, COMPETING TEAMS: DO YOU REALIZE THAT YOU HAVE GIVEN THE POWER TO DECIDE WHAT IS GOOD POETRY TO FIVE ARBITRARILY CHOSEN PEOPLE WHO WILL GET DRUNKER AND DRUNKER AS THE EVENING PROGRESSES? DO YOU REALIZE THAT THE DECK IS STACKED AGAINST YOU IN AN OBSCENE NUMBER OF WAYS? IF YOU REALIZE ALL OF THIS, WILL YOU PLEASE SHOUT WITH CONVICTION: IT’S A FUCKING SLAM!

Holman continues with inspired froth:

“because Pepsi and Nike have conflicting ideas about slam team uniforms …

because Patricia Smith has more truth in her little finger than an entire

Boston Globe front page …

because rap is poetry and hip hop is poetry …

because local heroes finally have national community…

because best poet always loses!!!”

A tsunami of noise washes over the auditorium with echoes of echoes, as the lights go down and come up on one solitary mic when a disembodied voice commands:

LET’S GET RRRRREADY TO RRRRRRRUMMMMBLE!

“We gonna get it on, because we don’t get along!”

– Muhammad Ali to George Foreman

I arrive at Austin’s Ruta Maya cafe on Thursday, August 20, for a preliminary bout in the 9th annual National Poetry Slam. It’s the biggest such event yet, with 45 teams (of four people each) competing for the grand prize of $2,000, plus 14 additional individual competitors going separately for $500. Poets from across the U.S. and Canada arrive here upon qualifying in local and regional competitions held throughout the year at home-based reading series. For many, the national slam is a pilgrimage that draws repeat contenders, but for others it’s a brave, new world, as with the New York City team based out of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, which generates new teammates every year.

Arguably, the slam’s origins are co-terminous with poetry itself, but the slam as a distinctly U.S. phenomenon goes back to the ’70s and ’80s when hard-nosed midwestern poets experimented with taking poetry from salons to saloons. Former Chicago construction worker Marc Smith was one of those poets who helped breathe new life into poetry after experiencing stale literary and academic gatherings where the spoken word was treated reverentially, like the word of God. In dada-esque reaction, Smith and others organized events in which poets donned boxing gear and sparred in wrestling rings where they honed the art of verbal one-upmanship. Smith encouraged the crowd to voice consent or dissent with the poet’s vision, or to just howl drunkenly if that’s what they felt like doing.

By the mid-’80s, Smith had launched a regular weekly slam that eventually found a home at the Green Mill (Al Capone’s former speakeasy, by the way). From there, it spread to the coasts, and the Chicago style of performance poetry was cross-pollinated at newly christened slam cafes and bars across the country. It wasn’t long before the first national slam competition convened in San Francisco in 1990.

I think about the slam’s humble beginnings when I elbow my way into Ruta Maya’s packed environs full of young scribes-wanting-to-be-oracles chomping at the bit for a piece of the action. When all of a sudden, I’m asked to be a judge for this bout between San Francisco, Roanoke, and Seattle. Should I remain “objective” or dive in head first? As the constant refrain, mantra, and all-purpose disclaimer goes: it’s a fucking slam!

Five judges are chosen randomly from the audience to give an Olympic-style score of 0-10 for each three-minute reading in four rounds, where each team member gets a reading slot. The high and low scores are dropped, and the remaining three judges’ scores are added. Poems over three-minutes long are penalized, and group performances are allowed in place of an individual reading. Props, costumes, and music are against the rules. Reading from memory is the norm, but scripts are allowed. The team with the highest cumulative score wins. Sounds simple, right? Before the weekend is over, these basic rules will serve as the nexus of debate, division, and unbridled animosity. Protest is as much the rule as the rules themselves.

The heat is on. Literally. Poems spit forth like steaming asphalt, fast and furious, increasing the Texas humidity with lip friction. Four-time individual slam champion Patricia Smith serves as emcee and introduces the judges: “this might be the only time you’ll want to applaud them.” I get used to the booing and hissing as if this article has already been released to a room full of poets. “Thanks for attending this bout at the hottest place on earth,” Smith jokes (she must not have visited SanAnto before). The bout closes with San Francisco on top (106.5 points), ahead of Roanoke (98.4) and Seattle (96.6).

The standout poem in this round is “Fallen Catholic Fix,” by SF’s Russell Gonzaga, a 29-year-old Filipino whose excitement at attending his third national slam matches his energy to win this year. We talk after the round and manage to sweat out the heat that will make poets faint throughout this weekend’s tournament.

Gonzaga teaches in an after-school program for mostly at-risk youth, a background he himself shares. The slam seems to be both a channel for and target of the rage he has worked through since his gang-banging days. He talks specifically about poetry readings for the slam versus poetry readings in communities of color: “I have slam work, and I have work that I do for the community, people of color, and I keep the two fairly separate. With a slam poem, I don’t get too spiritual. If I do, it’s interweaved with something that’s more mainstreamish, and that’s the one thing that’s strange about the slam: it’s defining a mainstream poetry, which is kind of odd.”

Addressing racial issues and other topics of importance to communities of color is a difficult if not self-defeating undertaking at the slam, says Gonzaga. “Subjecting oneself to the scrutiny of the dominant culture is one thing,” Gonzaga points out, “and not only that, they’re giving you number scores, which is even more problematic.” Paul Devlin’s excellent movie, Slam Nation: The Sport of the Spoken Word, documents the opinion at the 1996 national slam that poems on race from people of color score low. But then again, conventional wisdom says that the judges always suck, and the argument goes that the best teams are the ones who can win despite and because of this fact.

In fairness, Gonzaga admits that folks of color participate widely in the slam, and that only females won the individual competition up until last year, when Cleveland’s Da Boogie Man, a young black male, won the title. But the question remains: why divide oneself between work devoted to home community versus this relatively new community called the national slam? “I’ll describe it in terms of experience,” says Gonzaga, “my first national slam at Ann Arbor, Michigan, walking into an auditorium filled with like 1,000 people, to see poetry! I had never experienced that in my life.” Ultimately, he feels that he must support the slam’s popularizing and democratizing effects for poetry.

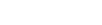

[Marc Smith, photo by Benjamin Ortiz]

Devlin’s film vividly captures the glory of poetry elevated by spectator flash, as the documentary follows Team New York City on its trip to the 1996 nationals in Portland, Oregon. The film’s title foregrounds the “sport” aspect of the slam, which makes sense since Devlin is an award-winning sports documentarian. But the film also does a good job of kicking different opinions around; some see the slam as a vehicle to advance literature, others see it as a poetry and performance hybrid art form unto itself, while others thrive on the slam as pure, no-holds-barred competition. Slam Nation also puts Marc Smith on camera, sagely suggesting that the slam works if it creates a community of poets.

But to get to the nationals, a year’s worth of local competition is

required, with poets keeping stats on themselves and others like running

backs. Poets sometimes “riff” on each others’ works, voicing criticism

often to the point of pissing each other off, and all the while provoking

each other to perform in top form like a race horse pushed to the limit,

requiring some element of strategy and even more stamina. Ultimately, the

slam is a community created by local and regional winners, who further put

the national gathering to the test of what community means and how it can

survive the contentious head butting that competition breeds.

Bob Holman, 1998 Team Manhattan slammaster (slamspeak for local

venue organizer), has been criticized and hated in some circles for

cheapening the slam and appealing to pure spectacle, as well as exploiting

gray areas (loopholes in rules). He helped found Mouth Almighty, the first

and only label devoted to spoken word artists, along with producing The

United States of Poetry for PBS and master-minding last year’s Manhattan

slam team, named Team Mouth Almighty, who won the championship. His

promotion of poetry’s commercial viability through corporate sponsorship

and merchandising has further been a source of controversy, with arguments

in his favor that this is merely an extension of the slam’s mission: to

popularize poetry. Sometimes, his emphasis on glitz and celebrity runs up

against Marc Smith’s blue collar character and emphasis on an honor system

in respecting rules.

But where does riffing cross the line between competitive edge, on

the one hand, and violation of a poet’s integrity, on the other? Where does

community give way to competition, that which both brings people together

and potentially divides them? Are rules to be taken advantage of, or

respected as law? Should the slam have a singular vision of poetic

integrity, or revel in creative division? When does poetry lose its

literary value and become pure performance? And how much corporate

sponsorship is too much?

These are questions that stem from the slam and fuel its fire,

questions that will never be answered definitively. But each and every

individual’s answers constitute a leap of faith in the slam that keeps them

coming back and contributing their diversity to the national community.

Community within community

Through light sprinkles of rain and ominous lightening, I travel

after the Ruta Maya bout with friends to Resistencia Bookstore, a haven of

progressive literary events proverbially situated “east of the freeway,” as

in the poetry collection of the same name by raulrsalinas. At 64, Salinas

is one of few remaining elder statesmen of Chicano poetry who has traveled

extensively to create networks of solidarity between African-American,

pan-Latino, and Native-American activists.

Part of his unofficial training in political and literary struggles

comes from Puerto Rican independentistas he met while imprisoned in the

U.S. federal prison system. Given the early passing of such poets as Jose

Antonio Burciaga, Ricardo Sanchez, and San Antonio’s own Jose Montalvo, the

reading for tonight will be an historic draw for Latinos from Austin and

SanAnto – Miguel Algarin, one of the founders of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe,

will headline a reading with the New York City slam team – all in “occupied

Mexico,” as Algarin calls it.

Straight out of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Nuyorican Poets

Cafe began in 1974 in Algarin’s apartment, where poets of the Puerto Rican

diaspora gave voice to a new urban identity captured by the term

“Nuyorican” taken up by now-legendary poets Miguel Piñero and Lucky

Cienfuegos. The Cafe sat closed for most of the ’80s but was jump-started

in 1989 after the death of Piñero, one of its co-founders. In partnership

with Algarin, Holman instituted the

cafe’s weekly slam and brought new life to the venue. Ed Morales, a Village

Voice writer who has worked with Holman, charts how the cafe became popular

to the point of super trendiness under Holman’s direction, and how it was

criticized for losing the Puerto Rican community base that was once the

founding principle of its existence.

“Algarin willingly allowed Holman to turn the cafe into a circus on

Friday nights when he ran the slam,” says Morales. Algarin’s taxing battle

with HIV and the demands of his professorship at Rutgers eventually took

his attention away from the cafe, where Holman was left to take credit for

its newfound notoriety. This was when relations between Holman and Algarin

became strained; Holman’s style began to supplant recognition of Algarin,

which made for a contentious relationship. Finally, a mutual schism over

Holman’s leave of absence to work on other projects got him booted in 1996

from the cafe’s board of directors. Morales admits that Holman helped make

the cafe a success in the ’90s, and that its original aesthetic has

subsequently evolved into the hip-hop ethos drawing the city’s young black

poets.

But tonight, at Resistencia, Algarin seems charged by the energy he

shares with the next generation of Nuyorican poets on the 1998 team. With

his left arm in a cast – reportedly from a street scuffle where he

interceded on behalf of a woman being harassed – Algarin takes the stage

with a jazz combo of saxophone and coronet to interpret poems by Salinas.

“Street corner dude makes jaaazzzzz Latino sounds,” Algarin intones with a

horn-trilled accent, as he simulates the cadence of congas, one-upping

Salinas’s Beat-jazz sensibilities with Afro-Latino rhythms and sensual

playfulness.

“I dare Raul to come up and read these poems better,” he says, in a

joking spirit of competition that forebodes the slam semi-finals coming up

tomorrow. Raul doesn’t take up the challenge, but instead he shares a few

poems before urging people to buy Algarin’s books and talk to him while

he’s still around, before they “catch the bus” with poets who have retired

from the struggle.

An open-mic reading begins, led by New York City slammaster Keith

Roach, who introduces the Nuyorican team and a host of other slam poets who

share in the evening’s festivity. A Nuyorican expatriate now on Team Los

Angeles, Gerrie B. Quickley arrives and hugs Keith Roach. Poets from

Montreal, Toronto, and Austin read until almost one in the morning despite

intermittent drizzle, sharing the calm of this community within the greater

slam community. It’s the calm before the storm.

Cold comfort community

I start Friday with breakfast at El Sol y la Luna next to the

Austin Motel, where poets are dragging themselves out of bed for a feast of

events in addition to the semi-finals bouts. Team Boston’s Gary Hicks, a

Christian Marxist who has a distinctive salt-and-pepper beard, joins in the

bouts today that will weed four finalists from the 18 teams who have made

the cut. “I’m in a state of existential shock,” says Hicks between coffee

refills. Today’s events include a head-to-head haiku slam, gay/lesbian

readings, and a “Chocolate City” showcase of African-American poets, among

many other open-mics and mini-slams. And then there’s the yearly softball

game, where poets prove they’re not true athletes.

But I head off to Book People bookstore to hear a reading with

Patricia Smith, emcee from the bout last night. I walk into Book People

just as the reading has started, and I notice that Smith is reciting her

“Note of Apology” that was printed in the Boston Globe following her

resignation as a metro columnist in June. Aside from being widely

recognized at the national slam as a pillar of this community and a slam

poet par excellence, she has also become known nationwide as the Pulitzer

Prize-finalist who admitted to fabricating characters and quotes in four

columns. In the note – her farewell column – the 43-year-old journalist

suggests that the ambition to achieve motivated her decision to “slam home

a salient point” from time to time with fabrication. “Finally, I’d like to

apologize to the memory of my father, Otis Douglas Smith,” she reads,

continuing with slight defiance, “and that’s his real name – you can check

it.”

Enthusiastic cheers issue from the crowd in obvious compensation

for the sense of loss Smith expresses. She mentions the support she has

received from the poetry community: “in the end, that was really the only

community that mattered.” Continuing to read poems laying bare what’s been

on her mind in the wake of the Globe incident, she admits to thoughts and

fears of the worst in moments of heartbreaking vulnerability: “My penance

is that I will keep living to see myself keep dying. I can see the

headline: disgraced, ousted, sinful ex-columnist just doesn’t get it. I

hide the gun on a bookshelf behind one painfully alphabetized row of poetry

volumes.”

Smith takes some time to switch papers, shaken somewhat. “Perhaps

you don’t understand. I am the face of American journalism slapping

journalism’s American face … I have been nationally declared a liar,

which means that this must be a lie and that me telling you that this must

be a lie must be a lie also.” Light, sympathetic laughter urges Smith to

keep reading with strength, but tears form at the corners of her eyes, as

her pained voice reads on: “These are words that I can still use: fluent,

funky, anemone, android, penis, shogun, sonnet, chisel, shield …. These

are words that I can still use: petal, candle, murmur, apple, tongue,

refrain.”

Now choking back tears, she forces the words to come out in a

litany, a catalogue of language she reclaims as her own: “scat, lullaby,

hands, adultery, vibrate, history.” She struggles to keep the string of

words coming, and then in thick staccato: “Man did not give me this gift –

man cannot take it away,” repeating this refrain to the point of

gut-wrenching emphasis, throwing her script to the ground, and finally

breaking out in tears that are met with open sobs from the audience. The

reading ends with a standing ovation and extended cheers.

Team Santa Cruz members Kelly McNally and Meliza Bañales openly

break down and cry with Smith. Afterwards, they say she’s a scapegoat in a

profession where journalists misquote and make far worse mistakes all the

time. Says Bañales, “She admitted she was wrong, and it takes a very human

person to admit mistakes. It’s also easy to demonize people for mistakes

because they’re in a public position.” From their reactions to her reading,

I wonder if they’re personal friends, but McNally points out that they just

met her: “She’s very open and giving, and she’s given us a lot of

encouragement since we’re only one of two all-female teams, and we’re going

into the semis.”

After the event, I head to Mojo’s cafe for a caffeine refill and to

see what’s happening next. I end up recounting Smith’s reading to a few

poets and an east coast slammaster. The slammaster voices a different

opinion on Smith’s appearance at this year’s slam: “She’s milking poets for

sympathy, because poets are dumb-asses. They don’t read the newspapers. I

mean, what she did wasn’t a mistake – it was blatant, calculated

fabrication.” Pointing out that there’s no need to fabricate material for a

metro column, he also clues me in to claims from the Boston Globe’s editor

that 20 more columns by Smith appear to have been fabricated. What’s clear

is that Smith’s career turn has become something of a rallying point in the

slam community.

Jivin’ with the pre-bout jitters

After the caffeine jolt, I wander over to Fringeware, a bookstore

next to Mojo’s, and run into Bob Holman chewing the fat with an old friend

of mine, Reggie Gibson. The 1996 film Love Jones was based loosely on

Chicago’s black poetry scene and featured poems by Gibson, whose

rhythmystical lyricism was a main source of inspiration for director

Theodore Witcher. Reggie has a bout this evening as part of Team Bellwood

(a Chicago satellite) and in the individual semi-finals, so we talk about

his strategy until a semi-finals update is posted in the windows of

Fringeware.

Very bad news: a computation error in scores has completely

rearranged the semi-finals bouts. Two teams, Santa Cruz and the Ozarks

(Arkansas), have been cut from the semis given the corrected scores, while

Manhattan and San Francisco’s Mission District team have joined the semis

bouts – all only a matter of hours before the bouts begin. I notice Russell

Gonzaga looking at the update. “This is bad – this is so very bad,” he

mutters exhaustedly. His San Francisco team will now go against Cleveland

and SF-Mission District, whose slammaster is one of his teammates.

Gonzaga mentions the possible conflict of interest his teammate,

Tarin Towers, has between her SF team and the Mission District slam, which

she organized to produce their team. He also claims that Team Mission

District formed when individuals didn’t make the San Francisco team, and

suggests that their representation of the Mission District (a once

predominantly Latino neighborhood newly gentrified) has negative racial

overtones. Team Mission District member Daphne Gottlieb tells me later that

the team formed legally under slam law, which 1998 National Poetry Slam

co-director Phil West confirms. According to West, the local Mission slams

did happen after the San Francisco slams, but Towers had contacted West

prior to the San Francisco qualifiers and approved the formation of a

Mission Disrict Team.

“It was known that both teams would be appearing at the nationals

for at least a month,” says Gottlieb, “[and] the Mission team thought that

any conflicts had been ironed out prior to departing for Texas.” But

Gonzaga maintains: “There remains doubt as to the truth of their claims of

having an open slam. Some sources in SF have told me that there were no

qualifying open slams for these spots, and that they never intended for

there to be any … I, and others, are convinced that there were no open,

advertised, public slams to qualify the three other spots on the team

[aside from the fourth spot slammed by Lauren Wheeler]. I voiced my dismay

with my team and the slam master [who] told us that the team was registered

and we could not protest the team unless we were directly affected by them,

in particular … I was content with this, being fairly sure that we

wouldn’t have to compete against them.”

He moans, “I don’t want to do this round,” but his teammate Omolara

consoles him and says “we knew this bout could happen, and it’s no big

deal.” Gonzaga doesn’t seem convinced.

Back at Mojo’s, an impromptu reading has started as poets from the

Chocolate City showcase spill out of the cafe. Reggie Gibson, Cleveland’s

Da Boogie Man (who is sitting out this year’s competition), Kent Foreman

from Team Bellwood, and others are sharing a circle of poetry like family

reunited, and the call-and-response style of some poets creates an

evangelistic revival atmosphere. Which reminds me: poets just can’t get

enough of poetry. This goes on for a few hours, through the mugginess and

threatening storm clouds, until Gibson announces, “Oh shit! It’s time for

semis!”

Smash-mouth poetry comin’ at ya!

The math error now pits Albuquerque against Manhattan against

Bellwood, a bout that should prove to make poetic sparks fly with the

talent lined up, and so I’m at Blondies, a skate store, where Albuquerque’s

Kenn Rodriguez is flexing for the match. He doesn’t seem visibly worried

about the re-match with Manhattan, who beat Albuquerque last year. “If you

want to win the national championships, you got to beat the nation,” he

says matter-of-factly. He mentions the corporate taint to the Manhattan

team, since they were sponsored by Mouth Almighty Records while other teams

had to hold fundraisers to scrape up money for nationals. And then there’s

the infamous incident last year when a Team Mouth Almighty member simulated

a penis by using a belt buckle suggestively, which tested the prop rules

but drew no penalty.

“We’re a pretty poor team, so if anybody should hate them, it’s

us,” says Rodriguez, “because we’re from one of the poorest states in the

nation. But you can’t go at it that way. Last year, we were built up with

hate, because a lot of people wanted us to beat them, but it didn’t help us

at all – in fact, it hurt us.” He sums up by saying that Albuquerque will

feel good about the bout if they perform well with integrity.

Team Bellwood’s Chuck Perkins, on the other hand, is in a state of

agitation. “I’m an ex-football player,” he grumbles with playful, mock

menace, and he looks the part with his shaved head and Fridge-Man frame.

“There’s terminology we use as ball players, like smash-mouth football. So

I’m out to let that transpire to poetry. I want, like, smash-mouth poetry –

I take no prisoners. I don’t play, and that’s why I dropped out of grammar

school: I didn’t like recess.” He busts up laughing and breaks from his

act, still talking about how a poet can step up to the mic with venom and

leave the stage sizzling. He’s here for the pure sport of it – that, and

the wine, women, song, and such that the national slam entails.

But it’s time for Perkins to show us the money. The teams draw for

order, and the emcee skips through the spiel repeated prior to every bout:

“A perfect score of 10 would be an earth-shattering text performed

perfectly, and a zero would be the worst poem you could possibly imagine

performed by someone who should not quit his or her day job.”

Manhattan’s Beau Sia takes the mic first and works himself into a

frenzy with a piece he read in 1996 finals: “When I get the money, I’m

gonna have iced monkey brain in Madagascar with Uma Thurman and Spock, and

me and Tarantino are gonna buy the bones of Bruce Lee and put them in a

movie called THE BONES OF BRUCE LEE ARE ALIVE … and I’m gonna be the

Asian male hustler on the Real World [on] Mars, and I’m gonna do sold-out

haiku poetry jams in Vegas! … when I get the money, I’m gonna own MTV,

and sure, money can’t buy you love, but love can’t buy you shit!” Manhattan

partisans whoop it up, urging him into more and more of a rabid recitation.

Different sides of the room ring with applause when the teams

rotate and poets step up, while coaches mark time with stop watches and

hold up color-coded cards to let the emcees know who’s on next. Albuquerque

takes the stage with a group poem: “From where I’m sitting, I haven’t seen

any poem that can make me feel safe at night … I haven’t seen any poem

that could feed, bathe, or clothe a homeless man.” Syncopated voices switch

off between the four team members lined up: “I haven’t seen any poem that

could stop police dogs from ripping chunks of flesh off a ten-year-old

boy.” Neck veins and pressured eyes bulge, as they comment on their

situation as poets, with dangerously close judgment of their own craft:

“when are we going to stop talking assertively and start acting

assertively? … when are we going to stop posturing behind staticky

microphones and finally start getting our pristine hands dirty? … I’ve

never seen any poem that could stop oppression … but I am ready and

waiting with an open heart and open mind.”

Manhattan comes back with a team piece pairing Amanda Nazario and

Beau Sia. In the performance, Nazario tries to convince Sia that he’s gay,

while Sia adamantly professes his heterosexual love for her – until she

asks, with the microphone demonstratively used for emphasis, “would you

love me if I had a dick? … If I was a man, and I had a dick, you’d touch

my dick?” Sia follows through the logic and breaks down, with Amanda

congratulating him on his admission.

[Amanda Nazario and Beau Sia from Team Manhattan, in Austin 1998, photo by Benjamin Ortiz]

The round stops, as the emcee announces a protest lodged by someone

in the audience: possible violation of the prop rule. Someone from the

audience utters, “sometimes a microphone is just a microphone.” The emcee

adds that Nazario’s performance slot was mostly taken up by Sia, and that

the authorship of the poem is in question which makes for another protest

by Albuquerque; Manhattan might have violated the authorship rule.

While the protests are being discussed, Bellwood’s Dan Ferri takes

the mic with a touching, meditative piece inspired by his work as a

sixth-grade teacher, speaking to the precariousness of young minds and

energy: “a room full of boys is a box full of mouse traps with a ping-pong

ball set on each spring aching for release … girls circle, gathering,

dancing new molecules, negotiating solar systems – they are a tag team of

young Venuses, I am a weakening sun.” After his reading, a friend of Team

Bellwood whispers to me that he should have read “The Bald Guy,” a

crowd-pleasing take on Ferri’s hairlessness. The judges score the piece,

which hovers around 8.7. Ferri walks out of Blondies with heavy emotion on

his face, recognizing that Bellwood won’t come back from this blow.

The emcee gives a protest update, mentioning that Sia’s

participation in the duet is legal if Nazario is the primary author of the

poem. On the prop protest, he reads from rulebook: “Generally, poets are

allowed to use their given environment and the accouterments it offers –

microphones, mic stands, the stage itself.” Interestingly, he doesn’t read

the part stating that the rule’s “intent is to keep the focus on the words

rather than objects.”

The bout continues with round four and another group poem from

Manhattan. “This is the great first line which sets the tone of the poem,

grabs your attention,” they announce while tag-teaming on lines in

self-referential commentary, “And this next funny line doesn’t let you down

– no, no, it’s funnier than that first line! … You see, the gist of the

poem is we’re writing a generalized poem because, because who can be

specific about a topic like ‘blah blah blah’?” They seem to respond to

Albuquerque’s impassioned plea for politics: “when suddenly the poem got

political,” they exclaim, while droning “POLITICS POLITICS POLITICS”

repeatedly, adding “Knock-knock, who’s there? Emotional manipulation,

snappy one-liners … leaving no button un-pushed – family: I hate my

father, I love my mother, I miss my sister!” With playful mocking of other

poems, they close: “This is the end line that makes you cream your pants

… throw your panties on stage, and: fuck me after the show!” Howls,

jeers, and semaphore of hand-gesturing incredulity burst from the crowd,

but the scores are in: Manhattan with 110.3, Albuquerque with 109.3, and

Bellwood with 106.8.

[Chuck Perkins from Team Bellwood, photo by Benjamin Ortiz]

An exodus of poets meets a crowd waiting for the next semis bout,

and as I make my way outside I notice Marc Smith surrounded by a gaggle of

poets evaluating the prior match. “It’s not about the writing anymore,”

says Smith, “it’s about how many different ways can you say ‘suck my

dick.'” I walk away with Dan Ferri and Reggie Gibson, who console each

other. Ferri is visibly upset, but enthusiastic: “We did what we did with

integrity.” Gibson answers, “I was so glad you dropped that piece! You

nailed that motherfucker!” Ferri agrees, “I wouldn’t have been able to

forgive myself if I had read ‘The Bald Guy.'” Ferri is talking about

nailing points versus staying true to the word. This is the double-edged

sword of combining poetry with performance, iambs with slams, writing with

shucking & jiving. A fan comes up and says, “your writing blew away

anything around you – you guys should have won,” and the Bellwood boys seem

consoled.

It ain’t over ’til it’s over

I’m at the Electric Lounge, the home of Austin’s local slam, for

the individual competition semi-finals. The place is packed, and few chairs

are available to the mostly standing audience. Organizers have brought up

an interlude of mariachis for “local flavor,” and I have to excuse their

ignorance to the truly Tejano sounds of conjunto because the mariachis are

doing a cookin’ version of “Jailhouse Rock.” Chuck Perkins grabs my tape

recorder so he can mock-interview some ladies, and so I head out to the

parking lot where poets are mulling over the semi-finals wreckage.

I marvel at the variety of backgrounds, persuasions, identities,

political viewpoints, and professions from around these states represented,

as folks sit on concrete abutments and talk shop. Congratulating Keith

Roach on New York’s triumph in their last bout, Albuquerque’s Danny Solis

also seems to comment on Team Manhattan when he says, “I’m so tired of this

soulless pop culture bullshit Real World MTV crap.” A few minutes later,

Bob Holman walks by Keith Roach, and they shake hands like old buddies. As

I walk back into the lounge, Tarin Towers rushes the door, citing a

“security problem.”

I squeeze my way back just in time to see scorekeepers tabulating

maniacally as people from the crowd jump to correct math errors. Reggie

Gibson takes the stage next, as he dedicates the following poem to James

Marshal Hendrix: “Burn it down, burn it down, burn it all the way down,

Jimi, make us burn in the flame that became your sound, Jimi, grabbing ol’

Legba by his neck forcing him to show you respect, hoochie man coochie man,

strangle him coochie hoodoo man, wrangle him voodoo child … and the

purple haaaaze ran through your brain and drained into the veins of

trippers, daytrippers turned acid angels by the gift of little wings from

you … and the musing brews of your sadomasochistic blues would ooze

through pores and LSD doors … one more time before it’s your last time,

brother … TO DIE YOUNG, TO DIE HIGH, TO DIE STONED, TO DIE FREEEEEEEE.”

He repeats this last refrain and wails into an air-jammed guitar

simulation, as the crowd jumps from their seats to affirm Gibson’s ultimate

number-one standing going into finals.

Back in the parking lot, poets sit in circles with backpacks like

cashed-out ravers, while New York and Albuquerque team members discuss the

protests against Manhattan. New York City’s Stephen Colman mentions to

Danny Solis that he once saw Beau Sia perform the duet from the semis bout

as a solo piece, which would bolster Albuquerque’s protest that Sia broke

the rules by being primary author of two poems performed. The discussion

gets heated when Colman says he doesn’t want to get involved in the

protest. Solis yells “fuck you,” as teammates restrain him and try to cool

down the argument. Kenn Rodriguez later tells me that “it’s not about us

getting into the finals. I think the Albuquerque team would gladly sit it

out if that’s what the slam community wants, because for us it’s about the

integrity of the slam and its rules.”

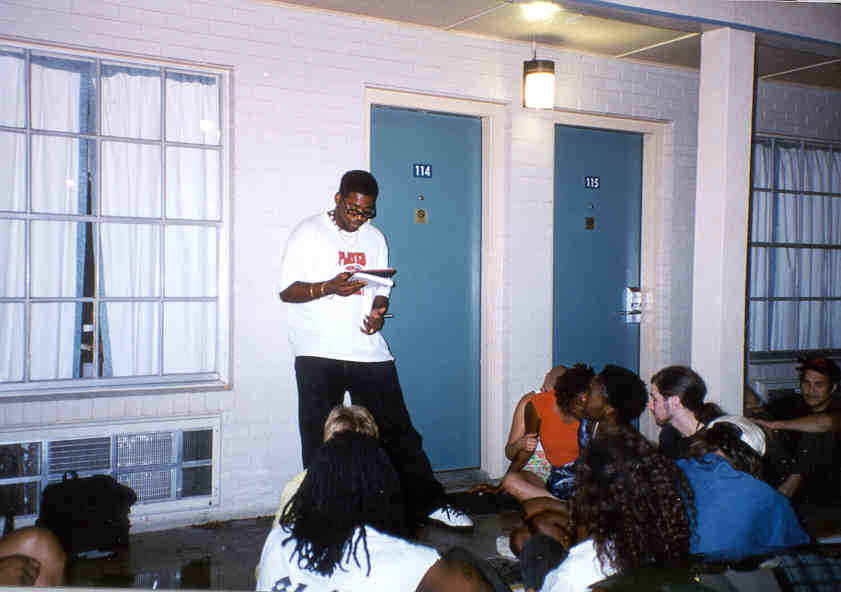

[Danny Solis from Team Albuquerque in Austin 1998, photo by Benjamin Ortiz]

On another front, Russell Gonzaga shows up with worry written all

over his face. It turns out that his match with the Mission District and

Cleveland turned into a score-settling blowout, after an attempt at a

formal protest against the Mission District failed. Deciding to read a poem

titled “Goodbye Kiss to the So-Called Western Civilization” especially for

that round, Gonzaga started off by saying “fuck the points – this is

personal: so-called ‘Mission District team,’ your deceit has broken my

heart,” and ended the poem with “I will make you wish you were never born.”

The poem went way over time, which destroyed San Francisco’s chances to win

– though Gonzaga had learned that numerically the two teams had little

chance of making it into finals anyway – and some of his own teammates

cried as he read the poem, which was perceived by Mission District female

teammates as a real threat of rape and physical harm.

The Mission District’s Eitan Kadosh argues that the poem itself was

a violation, commenting that “During the course of his meandering piece,

describing how much he ‘hated the Mission Team,’ he explained, in explicit

detail, how he would come into our homes and tie us to our beds, while

carrying out assorted acts of violence.”

Others, including Kelly McNally of Santa Cruz, suggest that Gonzaga didn’t

mean his poem as a real threat. “What I witnessed that night was not a

‘threat to rape and cause physical harm,'” says McNally. “What I saw was

the performance of a horrifyingly well-written poem that was designed to

elicit a response of emotional pain, which it did entirely too well, using

graphic images of metaphoric violence.”

Regardless, Gonzaga has gotten himself barred from walking into the

Electric Lounge tonight, and he says that Mission District teammates have

called the police. While we talk, Tarin Towers walks out, and Gonzaga tries

to call her over to explain himself, but she turns around and walks back

into the lounge with a hurried pace. Mission District teammates will later

stay up all night worried for their safety at the slightest sounds down the

hallway of their hotel.

Slammin’ Super-8 style

I, on the other hand, will stay up all night in a search for even

more poetry. Chuck Perkins insists on checking out the Super-8 Motel, where

Team New York City is reportedly chilling poolside. We head out with Da

Boogie Man and Cleveland slammaster David Snodgrass, a 29-year-old

industrial machinery worker with stringy hair sprouting from underneath an

oily baseball cap. It’s about 1:30 a.m., and Boogie repeatedly gets calls

and answers pages from Ohio on his cellular phone. “What’s up?” he answers.

“I’m at the national poetry slam, dog, like I told you!”

When we arrive at the Super-8, some folks have already dipped into

the pool, but they gather to start a round-robin reading. Poets riff off of

each other reciting treatises from memory, and Team Montreal’s Debbie Young

says, “Damn! We’re some poetry fiends here!” Just when I’m about to nod off

in a parking lot oil puddle, another poem starts up. The reading goes on

until about 5:30 a.m. when Kenn Rodriguez arrives with Albuquerque

teammates. He’s back from the protest meeting, where Manhattan was found

free from penalty. Kenn looks like death warmed over, and neither team has

made it into the finals.

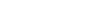

[Da Boogie Man from Cleveland, slammin’ at the Super 8, photo by Benjamin Ortiz]

The republic rolls out of bed

Despite last night’s revelries, everyone convenes at the Electric

Lounge at 10:30 a.m., dodging the light spritz that becomes a lawn watering

and later a downpour. Every participant is welcome to the slammasters

meeting, one of two yearly gatherings to decide rules and take care of

business. The other meeting happens in the spring in Chicago, where the

National Slam Executive Council presides. But this meeting is where

democracy in the fullest sense takes precedence, where every participant

can voice concerns and vote on immediate business. Less a formal convention

than a measuring of the communal vibe, this meeting is meant to take care

of the bad blood and conflicts that have come up before the slam heads into

finals tonight, where Los Angeles, New York City, Cleveland, and Dallas

will be competing for the championship.

Over bagels and coffee, participants take turns going around the

room to pose questions about what qualifies as an ongoing venue and what

qualifies as a team. Marc Smith, president-for-life of the national slam,

explains regulations in his down-to-earth nasally rusty Chicago accent. He

expresses discomfort with the idea of creating more rules on top of rules,

which is against the spirit of the slam.

Suggestions are made to hire independent auditors to eliminate math

errors. As comments go around the room, someone voices a hopeful “Peace for

all poets.” Everyone responds enthusiastically, but reports follow of slam

poets serving as judges in some of the bouts, a possible violation of the

slam’s honor system. More suggestions: David Snodgrass calls for opening

the national budget to scrutiny.

The issue of stripping during a performance is brought up, since

the option is not available equally to women as to men. That’s when Team

Austin’s Genevieve Van Cleve lodges a complaint against Clebo Rainey, a

Team Dallas member who ripped his shirt off during a semi-finals reading of

his poem “Rarefied in Arkansas.” Taking her own shirt off and standing

topless, she reads from a statement in an emotionally charged voice: “in

all his rarefied glory, no one would accuse Clebo of using his breasts to

get a better score or a better job. I know, the slam is not responsible for

righting the inequities of our culture … however … we must assure that

our words are not enhanced or underscored by a nakedness not available to

the entire community … I swear, if that shirt equaled two-tenths of a

point, if that shirt had stayed on my very very good friend’s body, I might

be on the stage at the Paramount tonight performing poems … The prop law

needs to be changed at slammaster’s in the spring.”

In her comments, she suggests that Team Dallas benefited unfairly

from Clebo’s stripping, though Team Austin member Ernie Cline comments, “We

lost to Dallas fair and square. The opinions Genevieve expressed about the

competition being unfair are her own.” Regardless, Van Cleve’s statement

opens a floodgate of issues to debate, including the prop and costume rules

and whether a new rule needs to be made. Marc Smith breaks in: “This is a

scenario where part of our community has to be sensitive to other parts; we

have to listen to what the women are telling us.” Attention then turns to

Rainey, a black-clad potbellied musician-turned-poet who drawls in

response: “last year at slammaster’s meeting this came up, and I stood up

and said to everyone, ‘Just tell me what the fucking rule is, and I’ll do

it.'” He mentions also that he had the poem and his stripping approved by

slam officials before he performed it. But for tonight, since the issue has

forced his hand, he’ll perform “Rarefied” without stripping, as a gesture

of concession to Van Cleve and Team Austin.

Cheers follow and die down when Russell Gonzaga raises his hand to

speak, apologizing to Team Mission District: “I’m so sorry for what I did

last night … I turned it into one of the worst experiences that I ever

had with poetry.” He apologizes to his own team as well, and admits that

his actions were inappropriate. Applause meets his apology, and afterward

people congratulate Gonzaga for his admission. One poet says that she had

been similarly insulted at a prior slam, but that no one had apologized to

her. Gonzaga accepts comments with a weary, defeated look.

Before the meeting moves on to deciding sites for subsequent

nationals, Danny Solis makes a statement: “This is a feast, and when you

have a feast, wolves will come. Some people want to make a living off being

in the gray area. So be it. But I think we need to … eliminate those

areas as a family, so we won’t be dishonored and exploited … I invite

everybody to put everything aside – if you had bad experiences, enjoy

tonight.”

Someone follows up with the comment, “watch what you say to the

press, because nothing is off the record.” He cites past coverage that

painted the nationals as an orgy of sex and drugs. “Don’t let them paint us

as degenerates!” From the back of the room, a chant goes up: “We are

degenerates!” As I walk out to catch some fresh air, I notice that Dan

Ferri has a T-shirt on that reads: “The points are not the point; THE POINT

IS POETRY.” Plato wanted to cast all poets from his republic, but what

about a republic made entirely of poets? This republic has met its on-going

crisis of legitimation, and has survived. Just in time for the finals

Meeting the master

Amid waves of chaotic aural overload, a jelly-roll-shaped white guy

in tights and a lucha libre Mexican wrestling mask with thick-framed

glasses holds up an individual slam championship belt heavy with fake gold

plating as the Paramount crowd roars to see El Poeta (as this year’s mascot

is known) get down and dirty with the rest of the poets. Skimming camp

humor from Mexicans rankles me a bit – especially since El Poeta’s Boston

accent mangles the pronunciation of his Spanish name – so I head out to the

lobby, where rent-a-cops are watching the doors like attack dogs. I manage

to convince them to let a few recognizable poets in without hassle.

Outside, faces are pressed with distortion against the glass doors,

as rain falls over an impromptu poetry reading with poets holding up a

banner that reads: “YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO BE LOUD.” The banner mixes with

cardboard signs announcing the need for an extra ticket. And there’s

scalpers – people scalping tickets to see poetry!

Back in the auditorium, a pre-competition poetry showcase includes

Amanda Nazario and Beau Sia doing the protest-drawing piece from

semi-finals. Before they can start, someone yells “NO PROPS!” This audience

hasn’t necessarily been following the whole event, so this comment is lost

on most, though it doesn’t pass without scattered snickering.

Phil West emcees the first few rounds of the team competition,

looking dead tired with the demands of keeping the slam running. After the

first round, New York City leads with 28.3, while Dallas follows (28.1),

with LA in third (27.9) and Cleveland trailing with 27.1. The second round

begins without missing a beat.

Dallas steps up with a group piece on phone sex, verbally and

physically simulating spankings and masturbation: “I’ll jerk you off with

my words.” In an interesting juxtaposition, New York’s Lynne Procope

follows with commanding presence and gravity in her words: “We be

pretenders, pretenders to the position of prophet, we don the mask of poets

late at night, and between the smokes of the lyrical jokes we slam up on

this mike.” Her serious tone plays off the hoots and hollers from the prior

piece: “we forget that this shit goes beyond Gil Scott, it goes beyond that

grand slam finals pot, this goes beyond all these half-ass rhymes you’ve

long forgot … everything we say must be the truth, because the innocents

are listening, and it will all be held against us, which we do not hold for

ourselves … do you know the definition of your revolution, or are you

just pretending when you step up to this mike? One-two, one-two: this thing

is on.”

At the end of the second round, positions have shifted slightly:

New York at 57.3, LA with 56.8, Dallas with 56.6, and Cleveland still

trailing with 56. Tension is high, but an intermission follows with poets

pouring into the lobby for drinks or outside for smokes. Vancouver’s swank

Ms. Spelt, a pale skinny boy, shows much love in the lobby with his taffeta

skirt, boa, and silky dinner gloves. Delirious embraces are exchanged, and

hallucinatory sleep deprivation makes for an edgy vibe when poets file back

in for the individual finals.

Marc Smith takes the stage to emcee, saying “My name is Marc

Smith,” greeted by a resounding “SO WHAT!” Patricia Smith joins him to

handle the six indie finalists who will go two rounds each for the

championship. Derrick Brown, from Laguna Beach, goes into an abstract

absurdist piece that thrills the crowd with its suggestive rhythm: “I am

the punk in your trunk and the if in your riff and the or in your gasm …

I am the tears extracted by Johnson & Johnson, I am the cuts on the fists

of Mr. Charlie Bronson … I am the last thing JFK tasted.” Brian Comiskey,

a roofer from Boston, reads a softly compelling poem on stealing car

stereos and how he became a poet – “the poet who once stole songs.” Reggie

Gibson repeats his Hendrix poem to a standing ovation and shouts of “10!

10! 10! 10!!!”

In an under-rated performance, Vancouver’s Cass King takes the

stage and endures catcalls at her appearance: “Nice dress baby!” She opens

with a rendition of “The Girl From Ipanema”: “and when she passes, each one

she passes goes: ‘HEY MOMMA, YO MOMMA, COME ON, WHAT’S UP BAAABEEEE!”

Strutting and dancing around, she explodes into a cabaret-style scat like

she was expecting to get heckled and had her words ready to counter, with

the crowd clapping along to her rhythm and rhyme.

In the second round, Roanoke’s Patricia Johnson expresses the most

volatile engagement of racial issues yet, bringing up the incident in

Jasper, Texas, and her own cousin’s violent death, challenging the audience

to right wrongs and be accountable. Her poem goes crushingly over time and

dooms her to last place, but Patricia Smith notes: “Sometimes you got poems

you just gotta do.” She also mentions that journalists Molly Ivins and Dan

Rather are in the house. Cheers and cross-cheers fill the house, with the

audience taking sides on who should win, but the championship ultimately

goes to Reggie Gibson, with Derrick Brown in second, and Brian Comiskey in

third.

“This is sadistic,” says Marc Smith, “we got these other teams

backstage waiting to come out!” They’ve been waiting for over an hour,

strategizing and deciding which pieces to throw at the crowd, anticipating

the other teams’ moves. Guy LeCharles Gonzalez brings another engaged poem

from New York: “Mumia’s plight is a hollow slogan to hook a poem on / as

the revolution is compromised by wannabe rap stars disguised as slam poets

/ pandering to the crowd / telling them what they want to hear / instead of

what they need to hear.” It’s an incredibly gutsy poem to read in a house

full of slam poets, especially with randomly picked judges, since Gonzalez

seems to take the whole slam to task for the art it produces: “You’re not a

poet, you just slam a lot / cram a lot of senseless rhyming / soulless

pantomiming / saying shit like Tommy Kills-niggers / ’cause it’s always

fashionable to lay blame elsewhere / especially if it’ll get a laugh and a

couple of extra points.” At the end of the third round, New York is still

on top with 86.5. Dallas follows with 85.7, then LA with 85.6, and

Cleveland with 85.3.

In the final round, Dallas comes back with a group poem: “Look, up

in the sky! It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s a bad motherf – SHUSH yo mouth!

I’m just talking about my black superhero, baby!” As the piece progresses,

they go through archetypes for a black, redneck, and gay superhero, as with

the redneck: “I’ll clothe myself in black, expose my butt crack, and walk

with the swagger of Johnny Cash!” Rising euphoria of the crowd makes the

house feel like everyone should jump on stage and join in the fun, and

rumbles of “10! 10! 10!!!” delay scoring. Team Dallas’s GNO rushes across

backstage like he’s flying during the cheering, which draws cries of “Team

Dallas is trying to influence the score!” No matter: Dallas scores a

perfect ten.

But it’s not over yet: for New York City’s final entry, Alix Olson

rushes the microphone, not letting the chaos die down from the Dallas

reading. Slightly hunched over and jabbing with her free hand, Olson

snatches the mic as if she wants to catapult her poem off the vibe from the

former piece, reading with furious energy: “it’s a remote control America

that’s on sale ’cause standing up for justice can’t compare to ‘I can’t do

it from a lazy chair’ … we’re closing out this country the way we began,

so step up for the hottest selling commodity – that’s right, no waiting

lines for HIV – condoms and needle exchange, they’re a hard-to-sell thing

for the right wing, so if you’re a junkie or a fag, rent to own your own

body bag – now, while America’s on sale … with buy one shmuck get one

shmuck free in the capitalist party, and there’s nothing left to get in the

way, of a full blue-light blowout of the U-S-of-A, there’s a know-nothing

back guarantee, a zero-year warranty when you buy this land of the freetos,

ruffles, lays – this home of the braves, the chiefs, the reds, the slaves,

so call 1-800-IDON’TCAREABOUTSHIT or www.fuckallofit to receive your credit

for the fate of our nation … where the almighty dollars sparkle and shine

in the Starbucks land, I’m proud to call it mine, but America’s selling

fast, shoppers – buy it all while you can, ’cause America’s been downsized,

citizens, and YOU’RE ALL FIRED.”

The scores pile in, and poets mob the stage when New York takes

first place with 116.2, with Dallas in second (115.7), Los Angeles in third

(115.1), and Cleveland in fourth (114.9). Debates will continue to rage

through the coming year about rules and definitions of poetry, and the

conflicts will never entirely be resolved. But the question, as Cass King

put it, remains: “I know it’s entertainment, but is it A-R-T – is it

AAAAAART?” That’s the leap of faith. But in this auditorium, through the

agony of defeat and the grandeur of victory, all of that has been put to

the side. These slam poets – the new griots, storytellers, shit talkers,

neighborhood sages, and village idiots all – replay and relive the communal

underpinnings of the spoken word. On this stage, they meet their maker, and

this moment is pure.

September 1998, San Antonio Current, Word: The Monthly Guide to the Arts in Dallas, and LiP Magazine

« Live Review: Antibalas Afrobeat Orchestra Live Review: Alejandro Escovedo »